05 Nov “Technical leakage fallacy”

“Technical leakage” and other fallacies

The 2013 T 1670/07 decision highlights several levels of counter-arguments used by the EPO Board of Appeals to refute arguments used by the Applicant to demonstrate the existence of a technical effect in the invention.

These counter-arguments give the impression of being used in the manner of vetoes preventing a more substantive discussion, so that it seems interesting to dwell on them and to question their relevance and/or weakness, before drawing from them some practical lessons.

1.The invention subject of the appeal

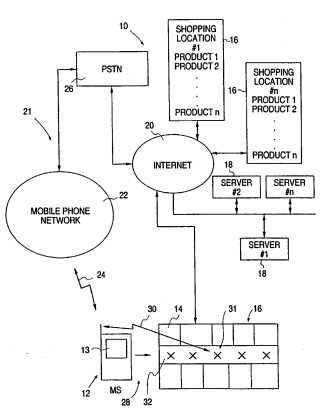

The European patent EP00960904.1, which is the subject of the decision T 1670/07, concerns the planning of purchases in different stores.

The invention essentially consists in the fact that the buyer enters the desired goods/services in a mobile device before making his purchases, then the mobile device determines and provides him – according to his user profile and preferences – with a purchase itinerary following a given order [optimal for example in terms of distance to be covered or purchase amount]. The buyer only has to follow it, i.e. to go to the various vendors provided in the itinerary to obtain the desired goods/services.

Before going any further, it should be noted that some features of the patent application must not have made it easy for the Examining Division to identify a technical effect.

For example, the title “Method and system of shopping with a mobile device to purchase goods and/or services”, which combines the two terms “shopping” and “purchase”, might have made the European Examiner think of a “business method”.

In addition, the invention as summarized above is very similar to what could be done with a simple pen and paper by a user who would directly use an Internet search engine and note down on a piece of paper the results of his searches in terms of price and location of the desired products.

2. State of the art taken into account

The state of the art closest to the invention was considered to be document WO99/30257 (D1) which describes a system for finding a vendor capable of fulfilling a customer’s order, based on the location of that customer.

The Board of Appeals considered that claim 1 of patent EP00960904.1 differed from D1 in that:

– (i) the user can obtain products from different vendors;

– (ii) the user is provided with an itinerary with an order to visit the vendors, which is based on a user profile.

It should be noted that the formulation by the Board of Appeal of the differentiating feature (i) as a mere result, and this by isolating it from the technical interactions that allow this result to be obtained, places us de facto in front of a conceptual feature. Then, it becomes easy to declare it as non-technical.

3. Technical leakage fallacy

The Applicant did try to put forward the technical interactions between the data relating to the group of vendors and the server 18, in order to highlight the production of a technical effect residing in the selection of the vendors, but the Board of Appeals brushed aside this argument by labelling it “technical leakage fallacy”. In other words, the Board of Appeals considers that it is not because the invention is implemented in an intrinsically technical environment (servers, cell phones…) that the technicality of this environment [automatically] confers a technical aspect to the whole process. This is the “technical leakage fallacy”.

The Board of Appeals thus finds that “vendor selection is not a technical effect”. Once again, a statement as broad as “vendor selection”, by isolating a feature from interactions with its technical environment, self-justifies its banishment from the “technical” world.

The Board of Appeals then considers that the interactions [relating to vendor selection] are not “sufficient” to make the overall process technical. This criterion of “sufficient” interactions used by the Board of Appeals obviously leaves one wondering.

Since the T 641/00 (COMVIK) decision of 2002, the actual question should indeed be whether the characteristics deemed non-technical, namely the vendor group data and the selection of vendors used or implemented in the computer system, contribute to an additional technical effect, i.e. a technical effect going beyond the mere classical effects occurring in a computer system.

The Board of Appeals thus seems to have taken a shortcut in its decision T 1670/07, not only by reformulating some features in a conceptual manner, but also by opposing the Applicant’s argument with the “technical leakage fallacy” veto. This is unfortunate because such a shortcut, which keeps the invention at a conceptual level, prevents further investigation of the potential technical implications and effects of the differentiating features of the invention, which could move these features from the category “non-technical as such” to the category “non-technical but contributing to the achievement of a technical effect through their interactions with the other technical features of the invention” and which should therefore be taken into account for the assessment of the inventive step.

4. Broken technical chain fallacy

In the course of its arguments in defense of the technicality of itinerary production, the Applicant unfortunately seems to have been led [by its exchanges with the Board of Appeals] to argue that the physical act [of the user] of moving from one place to another was technical in substance.

The Board of Appeals then took the opportunity to apply a second veto, called the “broken technical chain fallacy”, according to which the action of a user in reaction to a given information cannot be used to justify a potential final technical effect in a process, because this possible technical effect depends on the reaction and decisions of the user (being implied that the user may not react as expected).

To defend the technicality of an invention based on a user action is understandably dangerous; perhaps it would have been here more efficient to defend the technicality of the generation of an itinerary by focusing on the processing and organization of physical data, such as the location and distance between the previously selected stores, and not to involve the human action as a technical argument…

Having stated that the differentiating features (i) and (ii) were non-technical, apparently by implying that they did not contribute to an additional technical effect, it remained for the Board of Appeals to reformulate the technical problem by including the supposedly non-technical aspects in the formulation of the technical problem itself.

The technical problem as reformulated by the Board of Appeals then becomes to modify D1 to implement a shopping route that includes orders from different vendors. Of course, with such a formulation of the technical problem, all that remains for the skilled person is a simple programming activity to implement…

5. Non-technical prejudice fallacy

However, the Applicant argued in return that by relying on D1, the skilled person would not have arrived at the invention, because D1 made it possible to identify only one shop, and if D1 was used to find multiple goods, D1 would only work if the plurality of those goods were available at the same shop. This would either not happen or would require a long trip for the user…

To this argument, the Board of Appeals opposed a third veto, named “non-technical prejudice fallacy”, according to which the reasons for not modifying the prior art raised by the Applicant would be based on non-technical aspects.

Beyond the question of whether the arguments used by the Applicant are really non-technical in substance, it is still not clear why only technical arguments would be eligible to demonstrate the absence of incentive for the skilled person to modify the prior art. Indeed, it seems reasonable that the skilled person, as a human being, can be subject to different types of prejudices, some of which may be non-technical, such as the fact that a same vendor who offers all the products desired by a user may not exist or may be located far from the user…

In any case, the Board of Appeals considers that the question of incentive does not need to be asked since the instructions for modification of the prior art are, from its point of view, already present in the technical problem (which it has reformulated…). QED?

6. Lessons to be learned

The counterarguments of “technical leakage fallacy”, “broken technical chain fallacy” and “non-technical prejudice fallacy” studied above clearly show that, as far as possible, the Applicant should not allow himself to be locked into overly simplified definitions of the features of the invention, which would isolate them from one another and thus deprive them of their interactions with the other elements of the invention. Otherwise, these features quickly risk being reduced to simple abstract concepts and then classified as “non-technical and without technical contribution”, preventing them from being taken into account to assess inventive step.

Such an exercise is always delicate since there may be a tendency to simplify the presentation of the features of the invention to ensure that the Examiner understands the patent application correctly. Then, the risk becomes that the Examiner only considers the conceptual level of the features considered in isolation, without going back to the interactions of the features with each other, whereas these interactions could reveal the contribution of the features to an additional technical effect…

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.